Vegan Artists of Whangarei

Ian Duffield explores the artistic emminations of the North, speaking to artists Lynda Bell, Rohan Bell and Richard Duhs about their motivations, practices and the intersection of art and veganism.

“Veganism is truly a kickass ingredient to liberation.” — Rohan Bell

The autumn sun filters through the kānuka canopy sheltering Whangarei’s Quarry Gardens, and the quaint collection of buildings which form the hub for a diverse group of Northland craftspeople and artists. I wander through the warren of rooms and studios to search

out the gaily-painted entrance of Lynda Bell, who with husband Rohan Bell, and Richard Duhs, form a trio of local vegan artists, whose work is celebrated by Whangārei’s vegan community.

Lynda’s studio is adorned with all the accoutrements of a flourishing artist: paintings (finished and unfinished), drawings, easels, books, cards, calendars, and the all important coffee pot. Lynda is best known throughout the North, and the wider vegan community, for her paintings depicting animals, usually in scenes which evoke in the viewer a multi-level connection with her subjects.

On the day of my visit to her studio, The Magicians sits in prominence on her easel; a magnificent bull conducts a meeting in preparation for a festival with his friends. For me, in the collection of animals depicted, there is an echo from childhood memory. I recall my family’s illustrated version of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, in which characters like Mole and Badger, Toad and Rat reveal their feelings and personalities.

I dare say they are the best feelings of humans, including kindness and goodness, displayed with simplicity when they work together and engage in simple tasks to overcome the problems of everyday life. When I talk to the trio of artists about their main influences and how their styles have evolved, each describes the creative process in different ways.

Although they have all had formal art training, they largely consider themselves to be self-taught, especially with regard to technique. And clearly they most admire other artists who are self-taught. As Rohan says, such fellow artists “have found something and, with a need to explore, will go all out to capture it.”

The creative process

Lynda’s approach is very intuitive, for she begins with random strokes of colour and patterns until ideas or images form in her mind. As her muse fastens to the topic, these evolve and may change considerably. “The drawing is always loose and messy, as I like the paint to

dictate how it will end up looking.”

In The Magicians, the background was inserted with swirling strokes (as an early sketch shows), leaving space for the main subject and his assistants to be added in detail at a later stage. Each of Lynda’s subjects has a story written to complement the painting, which she has collated in a book entitled Rainbow Dreams and Tea Parties, the Art and Stories of Lynda Bell.

The story of The Magicians centres round the Highland Wizard (aka the bull) and his meeting with friends to plan a ‘Festival of Hope’, which will happen after the rise of the yellow moon and be attended by magical creatures from far and wide. Their magical hope will be bundled up and carried by birds to all corners of the Earth. “Have you ever felt that sudden spark of hope and energy and a feeling that everything will be OK?” the artist asks.

For Rohan, the creative process is somewhat different. He works primarily as a chef at the popular vegan cafe Power Plant, and snatches time to paint whenever he can manage. There are strong vegan themes running through all his works. In his work he wants to show “how naturally veganism accords with nature’s laws and mythologies” and, even more significantly, how it offers a vital pathway back to a healthier, more equitable and abundant world. In Rohan’s own words: “I happen to love drawing, and all my best ideas about a better world happen when I’m drawing.”

In such moments, he begins with a loose feeling about a subject.

“I try to keep the mind away from ‘trying to figure it out’, like an answer to a question. I then trust my technical abilities to bring form and quality to the work and its meaning.” He believes that anyone can be an artist, imagining “empty space, waiting for inspiration and aspiration”.

Rohan is especially inspired by the writings of bell hooks, an author for social justice and feminism who “takes power from the dominant oppressive ruling class of our times and dismantles their systems and power to give back with positive perspectives and empowerment to the outcasts and underprivileged”.

Rohan’s multi-faceted Robyn Hood, a pencil on wood drawing, portrays the image of bell hooks, spliced with key words from the lyrics of songs by Natalie Merchant,

all mingling together in a serene vegan world in which people are living in harmony with animals and other creatures in nature.

Richard‘s focus is bound in his ideas which complement his veganism. He has a strong belief in conservation and recycling, and has been accumulating materials which can be used in his art, such as masking tape, cassette tapes, artificial Christmas trees and framing, all of which have been discarded by others as rubbish.

He points out that his former tutors were critical of his using such resource material, because of their “impermanence”, but he has found ways over time to make them more durable as well as using them for subjects which suit the fragile states, such as self-portraits and dreamscapes.

For example, cassette tapes form the surface of his signature tape-drawings. Similarly, the Christmas tree material is adapted for his distinctive sculptures, a few of which, like The Green Buffalo Way, are currently displayed prominently in a previously vacant space in Whangārei’s Strand Mall. His sculpture Lorde and a Racing Boat was also exhibited at Whangārei’s Cafler Park during the ArtBeat art festival.

For Richard, the creative process is embedded in the trust that his artistic path will intersect with the opportunities he needs. “I am lost for nine-tenths of the process of creating, and rely heavily on a concluding chapter to make sense of the search. Even an outdoor sketch with people walking higgledy-piggledy over the course of several hours may only unite into a line of sight at the last moment, with an observation that seems so surreal that I feel life is imitating art, and that my role as an artist has been won.”

The animal in art

Men and women have been captivated by the power and beauty of animals since earliest times. Stone Age artists captured their vibrancy with images in caves and tribal artists from many cultures combined human and animal features to symbolise our bond with the natural world. Vegan artists, like those in Whangārei, offer an extended dimension, and although they work under constraints (and extra expense), with their paints and materials, the vegan ethos generates the energy which surges through the circuits of vegan artistry. For many artists, there is a profoundly empathetic connection with animals and an aspiration to capture it in another dimension.

Richard, while sceptical about art being classified as ‘vegan’, has an individual perspective on this relationship. He feels more layers of connection with animals that he can draw or sculpt by seeing them in a fight for survival (which he wants them to win), than he would if they could only lose.

“I hope this means more life is caught in my art, right down to the animal’s tail… I want to show the animal as emotionally free, rather than psychologically caught.”

Art, as Rohan emphasises when we discuss this aspect, focuses around varying layers of communication. Those who might underscore their own abilities as communicators can generate powerful ideas and emotions as artists. He makes a compelling analogy to musicians who, despite talking little about their work, can evoke powerful emotions with their compositions.

Rohan admires Lynda’s “comprehensive vision and abundance that is saturated in the qualities she believes in as a vegan artist, like compassion, kindness, beauty and love”.

Lynda has joined an international group called The Art of Compassions Project, which motivated her to make compassion-inspiring art. This influenced the theme of many of her works and has given her greater purpose beyond being a full-time artist.

“I could see that every person has goodness and kindness in their hearts and I wanted to awaken that in everyone who saw my art.”

Idyllic images, like people embracing animals or animals and birds enjoying freedom in a natural setting, are a recurring theme of vegan art. They may be both beautiful

and inspiring, and appeal directly and emotionally to viewers. Sadly, the opposite, such as animals cowering in cages or those in the process of slaughter, we find repelling and these are often proscribed by vegan websites as their viewing is deemed too painful. As Lynda says, such images are “sometimes extremely hard to view, it can be confronting and horrifying.”

That, of course, could well be the reaction which the artist is trying to provoke — perhaps it is timely to re-evaluate your personal ethics and reject such systemised cruelty.

Viva la liberation

There is another thread which percolates through vegan art: the theme of liberation for both animals and humans. Rohan cites the example of Lynda’s work, The Protector

and The Guardian, which when it went viral, creating excitement in many countries when viewers identified with the vegan messages in the painting. Liberation is not solely for animals; the role of the artist is to foment individual liberation as viewers respond with emotion to the artist’s vision. Or, as Rohan declares: “veganism is truly the kickass ingredient to liberation.”

Vegan painting is surely concerned with compassion and animal sentience, but it also aligns with a much wider activist movement, including street and poster art, magazine and music art, all of which identify with the broader goals of collective freedom and liberation.

“We are seeing how connected we all are, and we hold each other’s freedom collectively,” says Rohan. “Artwork hits a vein and triggers an identification to the (vegan) movement, that we all feel together.”

More from the artists

You can see more of Lynda’s beautiful creations at her website, artbylyndabell.com, or by

following her on Facebook @lyndabellart and Instagram @lyndabell_art.

Later this year you’ll be able to see Rohan’s work in an exhibition, entitled The Greens Apprentice, in Whangārei. Until then, catch him on Instagram @roboatbell.

Richard established Whangārei’s The Myrrh Gallery in June 2020 and you can keep up to date

with him on Twitter @richard_duhs.

Aotearoa Vegan and Plant Based Living Magazine

This article was sourced from the Winter 2021 edition of The Vegan Society magazine.

Order your own current copy in print or pdf or browse past editions.

Disclaimer

The articles we present in our magazine and blog have been written by many authors and are are not necessarily the views and policies of the Vegan Society.

Enjoyed reading this? We think you'll enjoy these articles:

Vegan Whispers in our Childhood Reading?

Vegan Whispers in our Childhood Reading? Ian Duffield dives into the canon of classic children’s books to explore the way animals have …

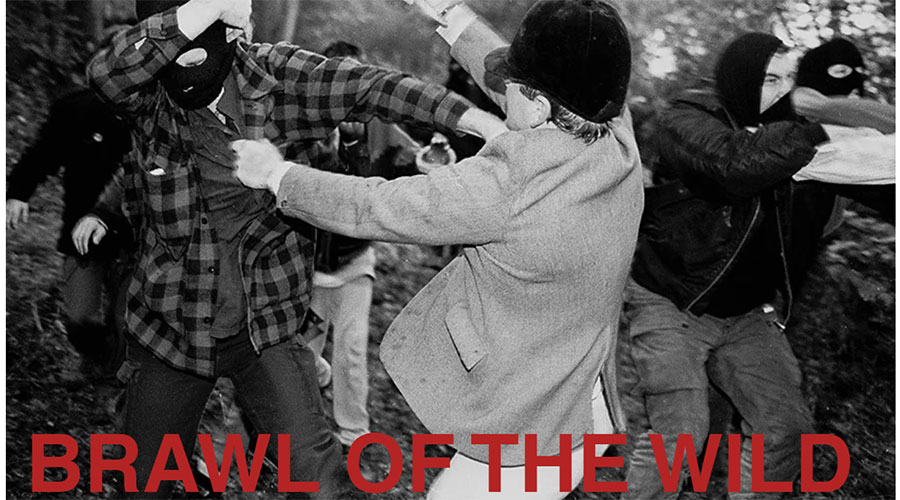

The Humanity Trigger

The Humanity Trigger First-time author Mark Fitzpatrick, AKA Mark Humanity, shares his war stories as a veteran hunt saboteur in Europe, along …

NZ’s Best Vegan Bangers

NZ’s Best Vegan Bangers Claire Insley, the Vegan Society’s media spokesperson, heads along to the NZ Vegan Sausage Awards, an annual celebration …