Vegan Whispers in our Childhood Reading?

Ian Duffield dives into the canon of classic children’s books to explore the way animals have been treated through literary history, asking if these stories perhaps contained the early echoes of a vegan ethos.

Animals have figured in literature since the serpent in Genesis tempted Adam and Eve to their amorous downfall, enticing them to eat the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden. The role of animals in metaphor and symbol is common to many religious texts, and writing 600 years before Christ, Aesop, in his enduring fables, wove animals into his stories both to entertain and to create lessons. Countless other writers since have built on the human love and connection with animals to explore character, and extend reader awareness and personal boundaries.

In traditional Western culture, literature and art were bound inexorably in Christian values, and children’s stories, increasingly available as printing costs fell and literacy improved, reflected the teachings of the church, often emphasising reward for virtue, and the converse for those who strayed from a righteous path (I think The Pilgrim’s Progress was the first book I just couldn’t finish). So books and nursery rhymes for youngsters were often laced with sinister characters (as in Hansel and Gretel), fairies, and demonic beings who preyed on the unfortunate. While children’s pets could be an integral part of a story, domesticated animals were usually viewed in a utilitarian way, the emphasis being on their food value, or ability to carry cargo for their human masters (especially in illustrations).

As the hold of the church gradually loosened over people’s lives, books for younger readers began incorporating adventure and fantasy themes, such as Gulliver’s Travels and The Swiss Family Robinson, and shortly afterwards stories with social themes, like Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, became part of the burgeoning literary scene.

Alice in Wonderland

Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, first published in 1858, had a volcanic effect on the style of children’s books. Among the other conventions Carroll upended, he included, to an almost absurd degree, the anthropomorphic behaviour of animals. Thus Alice is treated, among other events, to a rabbit checking his pocket watch, having animals throw rocks at her (the rocks turn into cakes), playing croquet with flamingos, receiving advice from a grinning Cheshire cat, and conversing with a very large caterpillar smoking a hookah.

The Cheshire cat acts as a classic narrator, providing a string of pithy and provocative comments, and confusing directives for Alice. A few even offer a glimpse of an animal rights perspective :

“I went to a hunting party once. I didn’t like it. Terrible people. They all started hunting me!”

Another favourite aside:

“I am not crazy; my reality is just different from yours.”

Alice not only embarks on a previously unimaginable adventure, but she eats foods, including mushrooms, and drinks potions to make herself tiny, and then large again. Her fantastical trip ‘down the rabbit hole’ has been used since that time as a pejorative term for anyone with an alternative view of convention.

Black Beauty

The background to Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty is interesting, as the author’s avowed intention was to promote a more humane treatment of horses. Sewell suffered a disabling accident when she was quite young, and as a consequence, spent much of her life helping her parents (her mother was an author of children’s books), and working around horses. Her sole novel is one of the best sellers of all time, with over fifty million copies sold.

The book is written in the first person from the viewpoint of Black Beauty, a well-bred colt, who begins life with kind owners. When they go overseas, he is sold and after a period of ill- treatment from various men, is eventually lucky enough to serve out his days peacefully. Sewell’s use of the first person method allows her to describe the treatment endured by Black Beauty and his colleagues, totally from an equine viewpoint. So we can understand why Ginger, a mare with a strong spirit, bites back when she is treated harshly, or whipped. In Ginger’s words:

“He had a cruel whip with something so sharp at the end that it sometimes drew blood, and he would even whip me under the belly, and flip the lash out at my head.”

After a serene early life together, both Black Beauty and Ginger endure the hard life of cab horses. For many of her young readers, Sewell crafts a tearful climax. In a scene full of pathos, Black Beauty sees, or thinks he sees, Ginger dead, being transported on the back of a cart.

The Wind in the Willows

Another masterpiece of the Victorian era was Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, a book which was captivating not only for children, but also for the adults who read the book as a bedtime story. Animals had been progressively taking on human traits and abilities; everyone is familiar with the adventurous Goldilocks, in which the three bears act as a normal human family, but also retain enough of their ferocious nature to terrorise the poor heroine for her home invading and porridge stealing at the end of the story. However Grahame’s story of the adventures of Toad, Ratty, Mole, and Badger widened his readers’ perception of animals. Some of the beauty of Grahame’s writing lies within his power of language. His heroes not only act with animal characteristics, but they display a complex array of human emotions and feelings, including friendship, empathy, dislike of spring cleaning (!), humour, wonder, and an appreciation of nature.

“Sudden and magnificent, the sun’s broad golden disc showed itself over the horizon facing them; and the first rays, shooting across the level water-meadows, took the animals full in the eyes and dazzled them. When they were able to look once more, the Vision had vanished, and the air was full of the carol of birds that hailed the dawn.”

Of course, these are very likely Grahame’s feelings for the natural world, but his story is so polished and convincing, that they are easily attributable to his main characters. For the animals, at least, nature contrasts sharply with ‘civilization’:

“Beyond the Wild Wood comes the Wide World,” said the Rat. “And that’s something that doesn’t matter, either to you or me. I’ve never been there, and I’m never going, nor you either, if you’ve got any sense at all.”

Grahame’s method was so engaging and successful that it was copied by other aspiring authors, and adapted by comic strip writers. An early model was the Rupert Bear comic strip which first appeared in the Daily Express after the First World War. Rupert lives a series of adventures and expeditions in Nutwood with his friends, many of whom, like the wise Bill Badger and gentle Edward Elephant, show an array of human qualities.

The Rupert Bear Annuals, which unsurprisingly seemed to be published each Christmas, included puzzles and games, besides the escapades of the animals. A typical cover of an annual in the 1950’s showed Rupert smiling down as he sails by in a hot air balloon. How inspiring for all his avid followers!

Rupert, ostensibly to save on printing costs, soon changed from being a brown bear, to a white bear (perhaps his Grandpa was a polar bear, and Rupert just grew like him, as he aged).

Later classics

Since that early era of literature classics, publishers and their discerning readers have been fortunate to have access not only to an expanding range of authors, but also to a talented and exciting group of illustrators. Post-war children’s libraries were dominated by English titles, but local writers, with local settings and subjects were soon subverting the British framework. Our dense, invigorating bush, our timeless harbours and estuaries and their inhabitants became the settings for a distinctively local group of writers (our whānau favourite was The House That Grew by Jean Strathdee).

In the writers’ realm, innovators have been so numerous that it might seem overly selective to single out only one or two. Eric Carle, for example, the renowned American author received universal acclaim for The Very Hungry Caterpillar, which munched its all-consuming way into another life as a butterfly. In part Carle’s success came not from just his colourful illustrations, but for the pop-ups which allowed his budding readers to explore with their finger tips the holes which the ravenous hero was creating as he devoured everything in his path towards a new life of sunshine and dance.

Undoubtedly too, the adaptation of children’s classics to film amplified the enjoyment of original readings. Popular books like Black Beauty were converted early to black and white film, but the advent of colour celluloid boosted the impact of already successful books like Watership Down. Here in Aotearoa, the film based on the successful comic strip Footrot Flats, with a soundtrack by Dave Dobbyn, broke box office records in the 1980’s, until eclipsed by The Piano in 1993.

Were there vegan whispers from those characters whom we loved so dearly? There were countless messages cultivating our kinship and love for animals. When Mole decided he would rather play with his friends than do his spring cleaning, it tickled the heart of every reader who felt disinclined to clean up a room. And there were strong directives about cruelty. The description in Black Beauty was so compelling that it became impossible for young readers to imagine striking any animal, whatever the modelling to the contrary by surrounding adults.

Sowing Vegan Seeds?

But were there vegan messages percolating into our consciousness? Perhaps, but those messages were muted, and with adult hindsight, funnelled by the constricted world view of the authors. For many of us, those authors suffered from the disconnected ambivalence which is still profoundly annoying today.

Acts of cruelty to our animal friends were proscribed, but nutrition was something quite separate and different. Few of the animals which starred in our favourite books were those which were routinely served to us on our dinner plates. Our favourite subjects were bears, horses, dogs, and birds, not chickens, sheep, pigs, and cows. Ironically, Footrot Flats, although based on comical incidents happening on a Gisborne lifestyle block, provided readers with a range of animals with inimitable personalities, including, besides the leading doggie character, Dolores the not-so-friendly sow, and Gussie the sheep — albeit a pet sheep, and presumably not destined for the freezer.

So for many of us, the amorality of slaughterhouses and dairy factories was hidden and disguised, and the vegan ethos filtered through only incrementally. However, it is an ethos which melds neatly with a more compassionate world than that which we grew up with. Caring for and nurturing the animals — indeed everything in our natural world — accords with many universal concepts. What many children feel intuitively for the animal kingdom melds perfectly, not only with Buddhist and modern Christian tenets, but also with Māori and Polynesian beliefs. Kaitiakitanga, in its most elemental and pure form, requires us humans to embrace and take care of all living beings. We are all part of the intricate fabric of life, and our supposedly superior use of technology behoves us to collectively create a more loving system in which all creatures thrive.

If you linger for a while in your local children’s library, you’ll see that the Famous Five have taken off to the gypsy camp, probably forever. The space is now repurposed with books from many lands, including our own, There’s a feeling of wonder and adventure; amid the splashes of colour, the oversized books, the picture books and the posters on the walls, the writers of Aotearoa predominate: Patricia Grace, Margaret Mahey, Joy Cowley, and a new generation of talented local writers celebrate our Kiwi lifestyle. Hiding over in the corner with the big soft cushions, well that’s Where The Wild Things Are, and there’s a large graphic of Rangi and Papatūānuku on the wall, celebrating the dawn of our universe. But be careful — Hairy Maclary might well be lurking behind the help desk.

Aotearoa Vegan and Plant Based Living Magazine

This article was sourced from the Summer 2024 edition of The Vegan Society magazine.

Order your own current copy in print or pdf or browse past editions.

Disclaimer

The articles we present in our magazine and blog have been written by many authors and are are not necessarily the views and policies of the Vegan Society.

Enjoyed reading this? We think you'll enjoy these articles:

Vegan Whispers in our Childhood Reading?

Vegan Whispers in our Childhood Reading? Ian Duffield dives into the canon of classic children’s books to explore the way animals have …

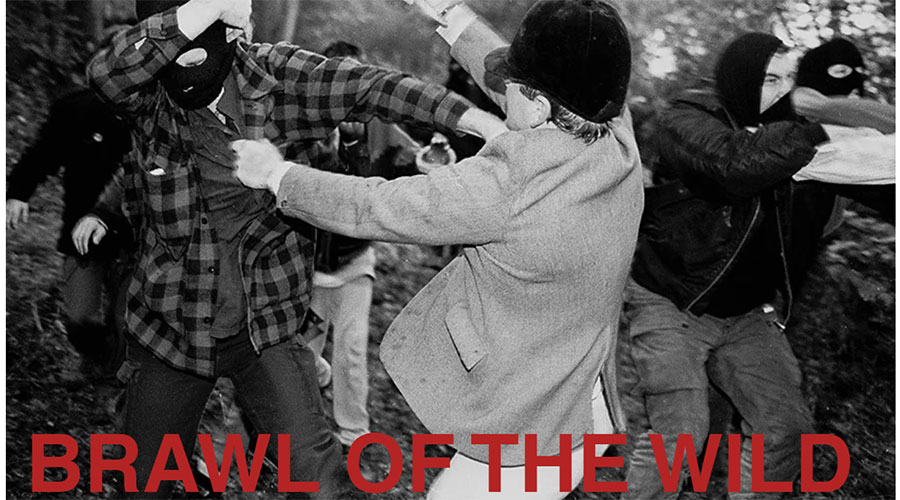

The Humanity Trigger

The Humanity Trigger First-time author Mark Fitzpatrick, AKA Mark Humanity, shares his war stories as a veteran hunt saboteur in Europe, along …

NZ’s Best Vegan Bangers

NZ’s Best Vegan Bangers Claire Insley, the Vegan Society’s media spokesperson, heads along to the NZ Vegan Sausage Awards, an annual celebration …